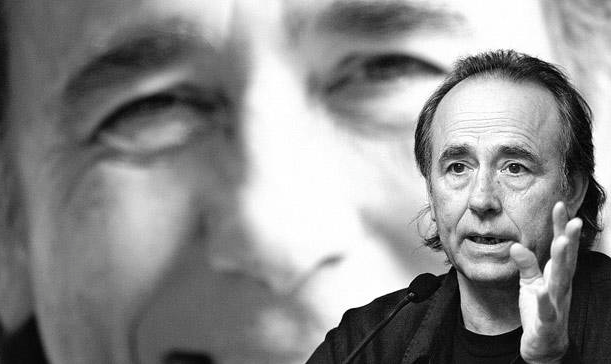

Joan Manuel Serrat is the subject of an extra special Spanish-style celebration.

The 71-year-old Spanish singer-songwriter, considered one of the most important figures of modern, popular music in the Spanish and Catalan languages, is being feted in Barcelona through a special project.

Serrat: 50 Years of Songs is the title of an exhibition that documents the life and times of Barcelona’s most famous musical son.

The show is a career-spanning homage to Serrat, the 2014 Latin Recording Academy Person of the Year, that highlights the singer-songwriter’s ties to Barcelona and Latin America.

The exhibition, at Barcelona’s Arts Santa Monica cultural center until September, includes photos, posters, records, Serrat trading cards and other fan memorabilia, performance videos, and, of course, music.

A parallel program of concert tributes to Serrat by other artists will run through the summer on a stage built into the exhibition, and the public will have a chance to perform their own song favorites during a series of scheduled Serrat karaoke sessions.

The show is set to travel to Montevideo’s Mario Benedetti Foundation later in the year, its first stop on a projected international tour.

“Serrat is more than a musician,” says Jaume Reus i Morro, director of Arts Santa Monica, which is housed in a former monastery. The Serrat exhibition is on display in the building’s vaulted stone chapel. “He’s part of the collective memory of several generations. Serrart has always been tied to the idea of freedom.”

Part of the show focuses on what in 1960s Spain became known as “the Serrat scandal.” Early in his career, Serrat was selected to represent Spain at the Eurovision Song Contest. After being told he was not allowed to sing in Catalan, his native tongue, he refused to participate at all. The episode established Serrat as a symbol of Catalan pride. His clashes with the Franco regime would continue, and after making remarks critical of the government in 1975, he spent a period in exile in Mexico, beginning his lifelong relationship with Latin America and his outspoken solidarity with repression and social struggles in the region.

The exhibition also reflects the lighter side of Serrat.

“I thought of the money, and the hope of a more satisfying sex life,” an accompanying text quotes the artist as saying, explaining why he wanted to be a musician.

A number of photos capture Serrat the sex symbol, with his chest bared under an open shirt and an inviting gaze. There are movie posters recalling a short-lived film career in titles like My First Love and The Private Teacher.

“I seriously believe that my biggest contribution to cinema’s evolution was to abandon it,” he quips in a text accompanying posters and gossip magazines.

Serrat admitted to being something of a hoarder at a press conference for the exhibition, and most of the objects and ephemera in the extensive display belong to him. They include his first guitar, which his father brought home in a paper bag, so that he would no longer have to practice on a borrowed instrument.

The singer’s roots in the working class Poble Sec neighborhood are captured in vintage photos, which show Serrat accompanying a black-clad elderly widow up the stairs, and a group of young men with red capes practicing their bullfighting moves in the street.

“I don’t know if young people today can relate to him,” he said, admitting that he himself had lost touch with Serrat’s music over the years. “But he is a myth. He’s like our Frank Sinatra.”